Space, scenography, drawing

Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

|

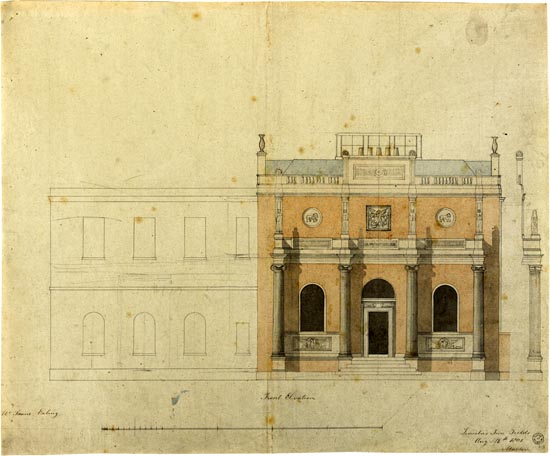

1. John Soane, main façade of the architect's house in Pitzhanger Manor Architecture and theatre During one of the conferences John Soane held at the Royal Academy he wrote that "the front of a building is like the prologue of a play, it prepares us for what we are to expect. If the outside promises more than we find in the inside, we are disappointed. The plot opens itself in the first act and is carried on through the remainder, through all the mazes of character, convenience of arrangement, elegance and propriety of ornaments, and lastly produces a complete whole in distribution, decoration and construction"1. This parallel with the theatre helps to convey the idea that a building is a single, complex entity and to understand it one cannot stop at the façade but must move inside it, consider the sequence of its parts, and link their different 'characters' (fig. 1)2. Soane's words continue on from the statements made earlier by Germain Boffrand in his Livre d'architecture: "Architecture [...] is capable of a number of genres that bring its component parts to life [...]. A building expresses, as if on the stage, that the scene is either pastoral or tragic; that this is a temple or a palace, a public building destined for a particular purpose or a private house. By their planning, structure and decoration, all such buildings must proclaim their purpose to the beholder". (Boffrand, 1745, p.16). Boffrand introduces the concept of the 'character' that a building can and must have, almost as if it were a character in a play. And, like a character, a building must be able to "reveal its character to the spectator" (Van Eck, 2007, p. 192). In 1788 Quatremère de Quincy wrote that a building can have "character", "a character" or "its character" (Quatrèmere de Quincy, 1788, item "Caractère"). This last option consisted in"assigning every building a state so suited to its nature or function as to make it possible to interpret, through its very evident character, not only what it is, but what it is not" (Quatrèmere de Quincy, 1832, item "Caractère"). Quatremère de Quincy compared a building "to a sort of play in which the scenes appear to change depending on the viewpoint, the changing play of light over the solids and voids throughout the day" (Quatremere de Quincy, 1832, item "Effet", p. 559). Recognising the 'character' of a building means assigning it human qualities that a spectator

can distinguish based on his own experiences and memories. The association of these images In a generalisation reminiscent of the classical

theme of theatrum mundi, Charles Garnier

went so far as to say: "everything that happens

in the world is nothing but theatre and

representation [...] The whole world is made

up of a continuous sequence of comic or

dramatic scenes, and nothing can be said or

done without involving actors observed by

spectators" (Garnier, 1871, p.2). This concept is linked to an idea

already proposed by Plato and, also, by Seneca

in his Epistulae morales ad Lucilium, and

also Epictetus in his Enchiridon. The concept

was reproposed later by Erasmus of Rotterdam

in The Praise of Folly (Vives-Ferrándiz 2011, pp.180-182) and in the

seventeenth century became a model used to

comprehend the existence of man.

However it was in the eighteenth century that

the theatre became a reference model for the

theory and aesthetics of art. It was then that

theorists saw themselves as 'spectators' who

observe the world the way you do a theatre3,

well aware of the subjective nature of one's

personal vision. At the end of the eighteenth

century reference to the theatre and the concept

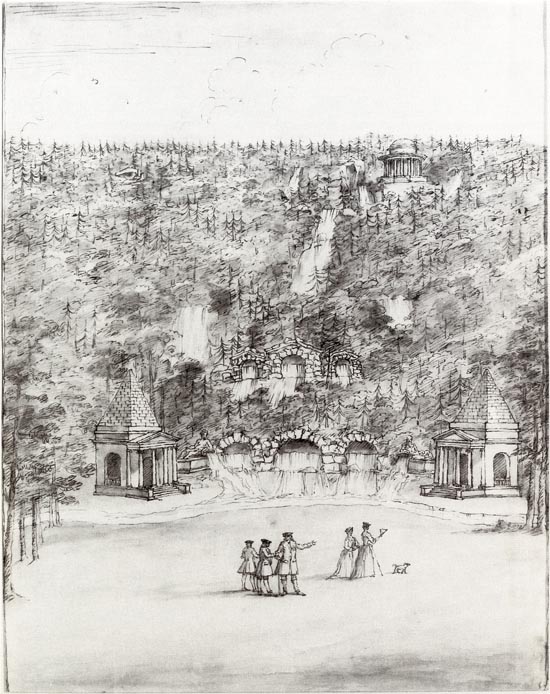

of character applied to architecture was present in the parks designed by William Kent (fig.

2)4, |

|

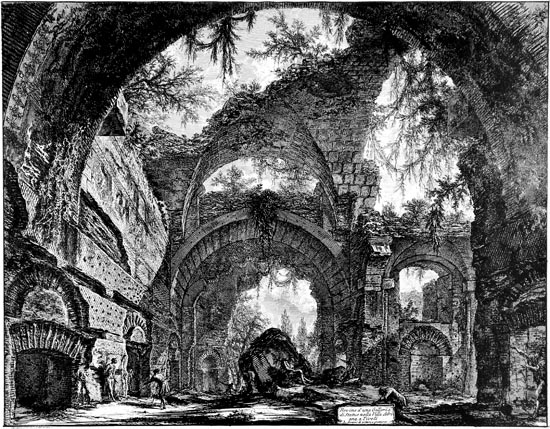

2. William Kent, proposal for the tree-lined hillside at Chatsworth Piranesi's imaginary images (fig. 3)5, the 'mysterious light' concept developed by Nicholas Le Camus de Mézières, or Étienne-

Louis Boullée's architecture of shadows. |

|

3. Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Ruins of a Sculpture Gallery in Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli Terms like 'theatre', 'scenario', 'decoration' or 'representation" were already used in books about gardening and landscaping in the middle of the century, especially during debates about the concepts of the sublime or picturesque. They were also used in aesthetic studies of the city and buildings, thus making the theatre a reference model for theoretical deliberations. This parallel with the theatre made it possible to interpret architecture as an 'experience' unity between the building and its context thereby underscoring subjective experience, sensations and perception. The interpretation required the active exploitation of images linked to an observer's previous experiences which, to be completed, needed a certain period of time. The goal was to 'succeed in seeing' not only what landscape architects searched for in paintings by Claude Lorrain, but also what Uvedale Pride appreciated in painters: "capable of seeing in nature what men usually do not see, [...] of recognising and feeling the effects and combinations of form, colour, light and shadow" (Price, 1810, p. xi-xv). Theatre and scenography Even if, one way or another, the use of this parallel has never been forgotten, in recent decades there has been a revival in the use of the image of the theatre due to renewed interest for rhetoric in art, communication, perception and experimentation. Contributions to this trend have been provided by Michael Fried, Richard Sennet, Helene Furján, Charles Bernstein, Richard Wollheim, Karsten Harries, Jonathan Crary, Harry Mallgrave, Josette Féral and Ronald Bermingham, Tracy Davis and Thomas Postlewat, Gevork Hartoonian, Louise Pelletier and, more recently, Caroline van Eck6. However, none of these authors actually consider the theatre as an artistic creation. Many of these contributions concentrate on painting or sculpture. In many cases the authors' interest focuses more on philosophy and philology rather than architecture. In others, even in older works, the theatrical analogy has negative overtones. In these studies the theatre is used because it provides a valid image with which to contemplate seeing and experimenting art or architecture. In many of these contributions the term 'theatrical' is used mechanically, without providing an explanation, and with sweeping generalisations that ignore the unique features of architecture. The fact that so many studies and approaches exist has led to a situation of conceptual ambiguity in which everything can be theatrical, but the theatre itself might not be (Eck, 2011, p.13). Although the analogy with the theatre is useful we must remember that mistakes can be made With this in mind, what exactly is scenography

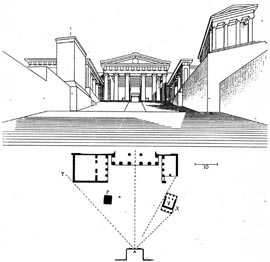

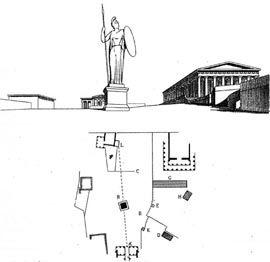

in relation to architecture? First and foremost Scenography and drawing A church, a concert hall, a lecture hall and a football field all have a very definite scenography, making it easy to understand where the actors and public will be positioned, how the action will take place, and what sort of action is involved. In Sloane's example the scene required visitors to move along the path designed by the architect so that they discover the viewpoints of the 'different scenes'. In his book Auguste Choisy provides another example. He interprets the area of the Acropolis in Athens as a landscape organised like a theatrical pièce(Choisy, 1899, p. 413-420), a series of 'scenes'8 created by multiple viewpoints and by 'perception' of the buildings from these viewpoints9. Choisy discovered the structured stage of a play in the Acropolis in Athens, an experience organised using four "tableaux" or "premières impressions" marking a ceremonial path. He wanted to demonstrate that the apparent disorder of the Acropolis actually reflected a landscaping logic10: the oblique arrangement of the temples and the relationships between the temples and their apparent incoherent composition create a stage where a ceremony can be held. To illustrate his analysis Choisy used four

drawings, representing four 'tableaux' (figs. 4,

5, 6, 7)11; each drawing has a perspective and

a planimetric diagram showing the position of

the viewpoint and outlining his theoretical

reasoning. |

|

|

|

| 4. Auguste Choisy, study of the Propylaea. |

5. Auguste Choisy, the first image of the Agora: Minerva

Promachos. |

|

|

|

|

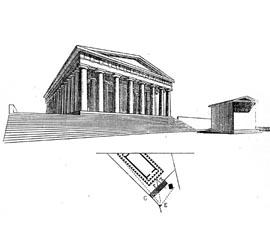

| 6. Auguste Choisy, corner view of the Parthenon. |

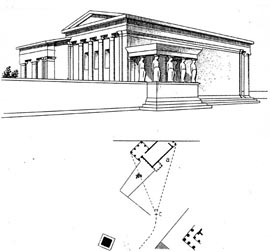

7. Auguste Choisy, the first image of the Erechtheion. |

|

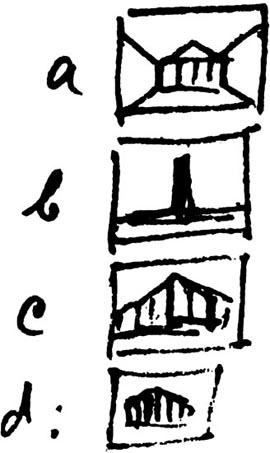

Based on Choisy's study and sequence, in 1938 the film director Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein corroborated this interpretation. He stated that the Acropolis in Athens was "one of the oldest cinematographic artefacts" (Eisenstein, 1989, p. 117), and illustrated his idea using a sequence of four scenes reinterpreting Choisy's four drawings (fig. 8)12. It would have been "difficult to imagine a more precise, more elegant and more effective structure than this sequence". (Eisenstein, 1989, p. 120). Although Choisy's drawings illustrated the salient points, the hubs of this theatrical arrangement, they did not claim to replace the consolidated image of the layout of the Acropolis. However, once published, a simple planimetric interpretation was no longer enough to truly understand its form. | |

| 8. Sergei M. Eisenstein, assembly

of the sequence of the four scenes.. |

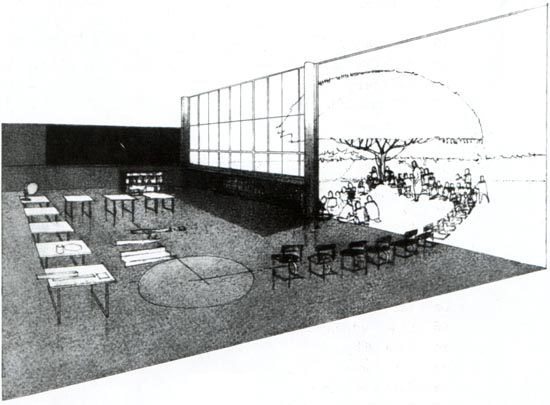

Drawing and scenography A drawing can reveal a scenography, as in

Choisy's case, but it can also be interpreted as

the description of a scene, representing it from

the point of view of the observer and revealing certain aspects hidden in the drawing. For example the one Richard Neutra used to explain

the way classrooms functioned at Emerson

Junior High School (Los Angeles, 1938) (fig.

9)13. |

|

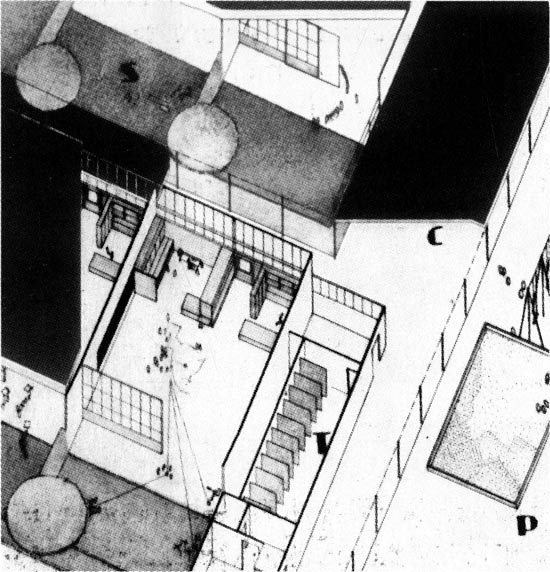

9. Richard Neutra, a classroom in Emerson Junior High School, Los Angeles. The lesson he portrays in the drawing starts in the classroom; we know this from the signs on the floor and several tables. This part of the lesson is undoubtedly followed by another one, represented by the curved arrangement of the chairs. The lesson now continues under a tree in the garden, with the students sitting randomly around the teacher. The sequence can be established starting with the signs on the floors and, above all, the curved arrangement of the chairs connecting what can be interpreted as the beginning and end of this activity. If one understands the unique significance of the classroom floor Neutra's drawing reveals much more than this: its perimeter merges with the edge of the wall, creating a single line. The viewpoint of this perspective is positioned on the plane of the wall and outside the classroom; it does not presume to represent what an observer would see if he was standing inside the classroom. His choice of viewpoint could reflect the penchant for unusual views tested by Lásló Moholy-Nagy or Alexander Rodchenko. In any case, it is a shift towards abstraction, a move away from traditional perspective simulation, making one think that the draughtsman did not intend to create a conventional perspective. Neutra uses this drawing to describe Maria Montessori's pedagogic method; he wanted to adopt it for some of the school's classrooms, just as he did in the Corona Avenue School (Los Angeles, 1935). In the latter school Neutra had illustrated the method using an almost diagrammatic drawing (fig. 10)14 demonstrating all the possible interactions, both inside the classroom and between the indoor space and the garden. |

|

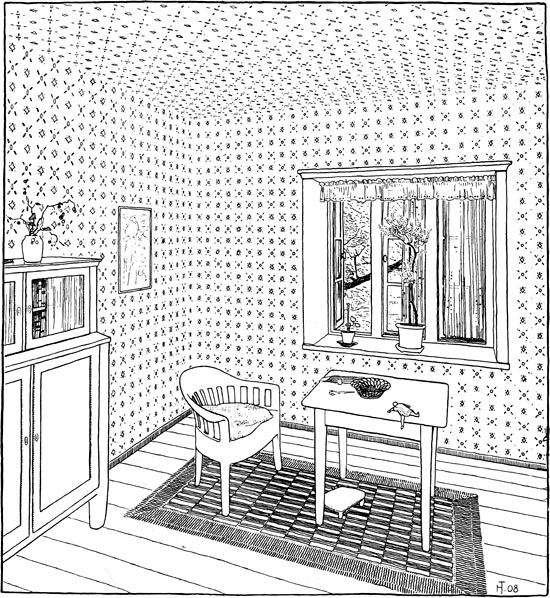

10. Richard Neutra, Corona Avenue School, Los Angeles. Neutra downsized these options in his drawing of the Emerson School and assembled them in a single sequence. Even if the drawing appears to be very different, it is still a diagram in which conciseness is the tool he chose to boost communication. The degree of abstraction in the drawing encourages one to interpret it more as a conceptual discourse rather than a scene. Another drawing by Heinrich Tessenow is more sophisticated. It shows a living room in a house designed in 1908 and published in Der Wohnhausbau in 190915 (fig. 11). |

|

11. Heinrich Tessenow, the living room. This ostensibly simple interior shows the corner of a room with wallpapered walls, a window, and a few pieces of furniture. Nevertheless, the drawing seems very detailed and important, even if nothing in it would appear to warrant such an effort. The clutter on the table in the centre of the drawing seems to indicate that a person was sowing, perhaps mending old clothes, and that a child was keeping the person company. Both have left the room, leaving everything as it was: the chair pushed back from the table, the sowing tools left scattered about, the doll with a leg dangling on the edge of the table, and the open window, as if it had been left ajar in order to be able to watch the child playing in the garden. There doesn't seem to be much else. Just typical

domestic actions that are not part of the usual

repertoire of architectural drawings. However,

the unjustified imbalance of the detail would Conclusions The link between the concept of scenography and drawing is clearer if, when viewing or interpreting a drawing, one bears in mind the importance of the way the drawing is positioned vis-à-vis the edges of the sheet of paper. This is even more obvious when there is more than one drawing on a sheet of paper. In this case the link between each drawing also comes in to play, as do the order in which they appear, the ratio between weights and measures, the way in which they convey the space, and the final character of the ensemble or ensuing aesthetic quality. Whether it involves the theatre, theatricality, scenography, picturesque landscape, cinematographic plane or rhetorical dialectics, all these images underscore the importance of the ensemble compared to the meaning of the dominant element. Bernini pointed out that this is because "things do not appear to us only for what they are, but depend on what is next to them, and this relationship changes what they look like". Accordingly, Bernini considered it was important to have "a welltrained eye to properly judge juxtaposed objects" (Fréart, 1885, p. 114), since interpretation depends on the effect it produces in the observer. These relationships allow us to recognise the limits of the graphic space around the drawing and the contradictions or ambiguities that require more in-depth consideration. Understanding that a drawing ends with the edges of the sheet of paper involves acknowledging the importance of the composition and relationship between the parts. The observer's active vision is what makes it possible to understand the meaning of the composition, proving that the information is absorbed in a continuous, progressive manner, and that the result lies in the unity created by the aesthetic quality visible in the design. |

|

Notes:

References: Addison, Joseph, 1711. [no title]. The Spectator, 1, March 1, 1711. Boffrand, Germain, 1745. Livre d'architecture… Paris: Cavelier. Choisy, Auguste, 1899. Histoire de l'architecture. Paris: Gauthier-Villars, Volume I. De Michelis, Marco, 1982. Una mostra sui disegni di Heinrich Tessenow. Impercettibili confini. Casabella, XLVI (483), pp. 36-37. De Michelis, Marco, 1991. Heinrich Tessenow. Milano: Electa. Eisenstein, Sergei M., 1989. Montage and Architecture. Assemblage, 10, pp. 110-131. Féral, Josette, y Bermingham, Ronald P., 2002. Theatricality: The Specificity of Theatrical Language. Substance, 31(2-3), pp. 94-108. Fréart de Chantelou, Paul, 1885. Journal du voyage du cavalier Bernin en France. Paris: Gazette des Beaus-Arts. Garnier, Charles, 1871. Le Théâtre. Paris: Hachette. Hunt, John Dixon, 1987. William Kent: Landscape Garden Designer. London : A. Zwemmer Limited. Lamprecht, Barbara, 2004. Richard Neutra 1892-1970: la conformación del entorno. Köln : Taschen. Piranesi, G.B., 1974. Vedute di Roma. fac. Unterschneidheim: Uhl, 2 carpetas, 138 lam. Price, Uvedale, 1810. Essays on the Picturesque, 1810, London: Mawman, 1810, vol. I, 404 p. Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine-Chrysostome, 1832. Dictionnaire Historique d'Architecture. París : Adrien Le Clere, vol. 1. Ray, Stefano, 1974. Raffaello architetto. Linguaggio artistico e ideologia del Rinascimento romano. Roma-Bari : Laterza. Rossi, Aldo, 1981 Autobiografía científica, Trad. Juan José Lahuerta, 1984. Barcelona : Gustavo Gili, 1984. Sack, Manfred, 1992. Richard Neutra. Zürich : Verlag für Architektur. Van Eck, Caroline, 2007. Classical Rhetoric and the Visual Arts in Early Modern Europe, New York : Cambridge University Press. Van Eck, Caroline, y Bussels, Stijn, eds., 2011. Theatricality in Early Modern Art and Architecture, Malden : Wiley-Blackewll. Vives-Ferrandiz Sánchez, Luis, 2011. Vanitas: Retórica visual de la mirada. Madrid : Encuentro. Watkin, David., 1996. Sir John Soane: Enlightenment thought and the Royal Academy Lectures. Cambridge : Cambridge University.

© of the texts Francisco Martínez Mindeguía © of the English translation Erika G. Young. This article has been published by the same author in the journal Disegnare, nº 55, Roma, 2017, pp. 12-21.

|

>> Back to the top of the page

>> Back to Dibujos Ejemplares de Arquitectura