STEVEN HOLL, Housing in Makuhari (Japan, 1992-1996)

Teresa Díez Blanco, Escola Superior de Disseny i Arts Plàstiques de Catalunya

|

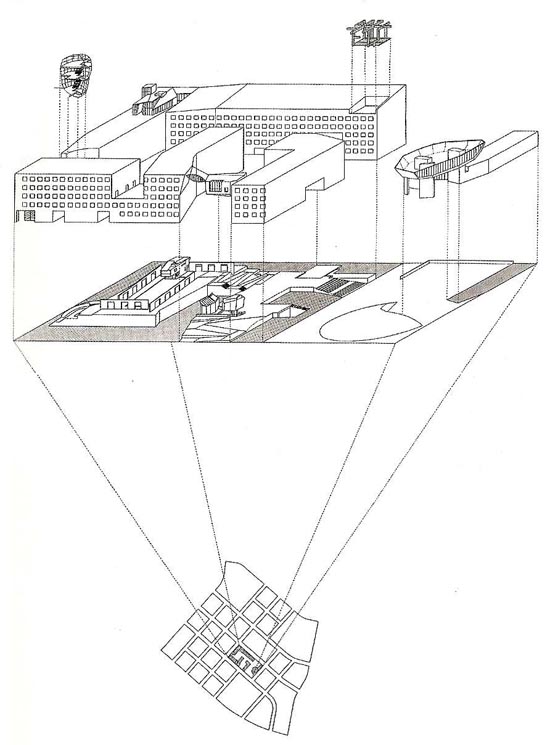

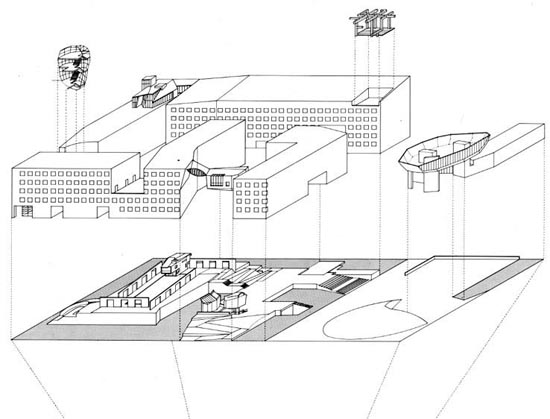

1. Steven Holl, Initial axonometric projection of the Makuhari project This illustration consists of a line drawing in cavalier projection, which is referenced to a site plan and exploded into its essential elements: apartment blocks, interior gardens and lightweight structures (pavilions). At first glance, three questions come to our mind: Why an axonometric projection? Why is it exploded? And finally, why a cavalier? This is not the only existing drawing for the Makuhari project, nor is it even the first one. However, it is quite typical of the period during which Holl used exploded axonometric projections as part of the representation of some of his projects. Gradually, with the growing use of new technologies in his studio, this method of representation was dropped in favour of rendering and photomontage. Axonometric projections are used to represent the building's shape because they allow the presence of the three dimensions in one drawing. The vision of shapes is direct, avoiding the mental process of synthesis of plan and elevations. It is not the normal human vision, but rather that of an observer placed at an infinite distance from the object. Therefore, parallel lines stay parallel in the drawing, without converging in a vanishing point. Because they show what a “distant” observer would see, axonometric projections are classified as objective representations of reality. Consequently, the first conclusion we can reach is that Steven Holl wanted to show, above all, the generated shapes. This is so because his project mainly consisted of designing the general shapes of buildings and the interior gardens in a city block. Thus, it was more of an urban planning project than an architectural one. The interior designs of the two hundred dwellings in this project were produced by other architects.

In exploded (or assembly) representations, the object is presented after being taken to pieces. These representations allow the viewer to understand all the parts of which the object is composed and the relations between them. They are usual in engineering or industrial design drawings. They are also used as explanatory drawings in instruction manuals for toys or furniture, showing their correct assembly process, even including all the details like screws. In an architectural context, they are used in diagrams showing the generation process or the main components of a project. In the Makuhari exploded axonometric, the building is reduced to its decisive elements and separated by levels, as if it were the result of overlapping layers or strata at different heights. Specifically, three different levels can be clearly distinguished: - One first level explains the block interior, showing the semi-public gardens which are part of the project and their different heights, ramps, and staircases. The ground is hatched in gray and the position of the first floor apartments is marked on the plan. |

|

- A second level corresponding to the main volumes (urban scale). It shows the linear blocks of housing, placed on the block perimeter. Their representation is minimal: basic shapes and main openings on the façade. Nothing else. They are drawn in a fine line, allowing for a lot more detail, which –nevertheless- doesn't exist. For instance, only the windows perimeter is marked, as if they were painted on the wall and had no depth. The roofing is marked as a white plane without any details whatsoever, except for those explaining the pavilions located on the next level. |

|

- The third level corresponds to secondary volumes: the pavilions (small scale). In fact, of the six lightweight structures, only two (those which are embedded in the linear blocks) are shown in this third level. Perhaps that is what justifies their placing on a third exploded level by Steven Holl. The rest structures form part of the first levels (gardens) and second levels (housing). It seems as though Holl did not want to segregate them, as if they were part of the stratum in which they appear. However, their levels of definition and detail are much higher than those of the housing blocks, even though they are smaller. |

|

Finally, the dotted lines connecting the first level to the second and third levels should be noted. They undoubtedly help to place and imagine each of the layers in which the project is organized in relation to the rest. However, these lines do not appear in exploded axonometric for other Holl's projects, like the Berkowitz-Odgis and Stretto houses, therefore making their understanding difficult.

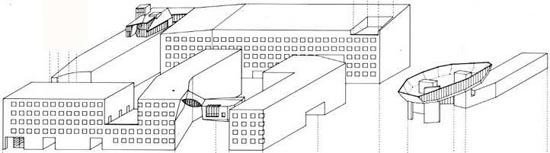

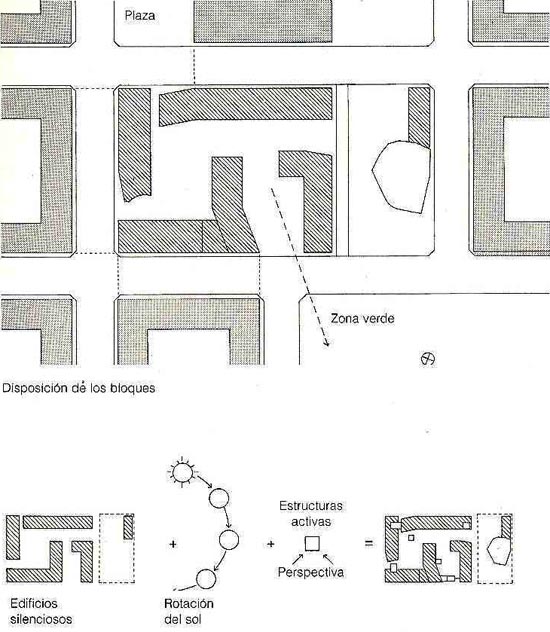

In the Makuhari housing project (1996) Steven Holl had to take on the demands on sunlight raised by the authorities, given that in Japan every home must receive a daily minimum of four hours of daylight throughout the year. Another restriction was that the whole project had to be built with reinforced concrete bearing wallso. The project brings together two opposing models: “silent and heavy” buildings and “light and active” structures. Holl uses the following comparison to explain his project: Lightness = Activity = Sound Heaviness = Limits of the blocks = Silence The silent buildings consist of six floors and house apartments, which can be accessed through semi-public gardens. Their structure is made of concrete walls, with thick façades and a rhythmic repetition of windowed openings. |

|

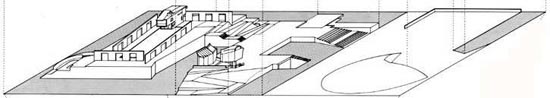

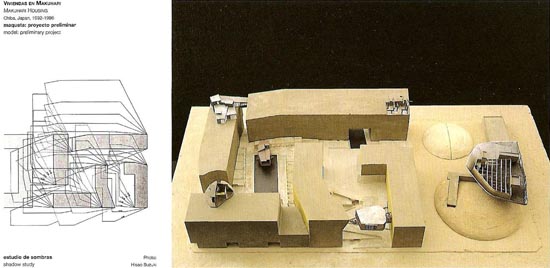

2. Sunlight study and model of the preliminary project for the Makuhari dwellings This general placing of the housing blocks is slightly altered in some places to provide a better adaptation to the sun's path by means of chamfered shapes and inflections, which allow more light to enter. There are also large openings on the ground floor, allowing access and views of the interior courtyards. |

|

3. Makuhari: Outline – Summary of the shape of the buildings in plan The next step was the insertion of six lightweight and “active” structures in the regularity of the housing complex as rupturing elements. Spread throughout the orthogonal formation of five blocks, which occupy the plot, these small pavilions are designed as a series of events in perspective, with a very specific purpose: to attract our attention and sight. That is why in the axonometric drawing the housing blocks are hardly detailed at all, so as to make them go unnoticed as the “silent buildings” they are. The pavilions, on the contrary, are explained in much more detail, their function being that of creating a counterpoint to the basic forms of the housing blocks, creating perfectly framed views and so “activating” the spaces, In Steven Holl's own words, walking through the gardens, at least two of the activating structures can be seen at any given point. |

|

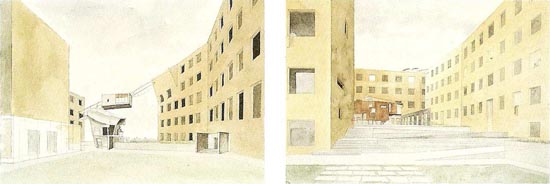

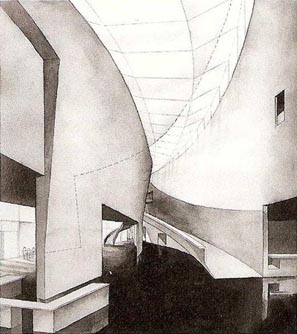

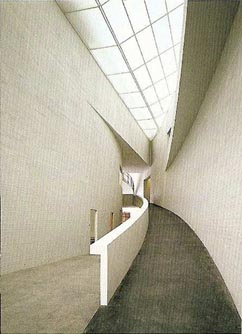

4. Steven Holl, Makuhari: Watercolour perspective studies of the preliminary project In fact, the interior gardens and the perspective organization of the “follies” -as Kenneth Frampton calls them in a clear allusion to the English picturesque garden- create a “journey of soul purification”, given that Steven Holl approached the commission based on the prose poem by Matuso Baso “The Narrow Road to the Deep North” which describes a pilgrimage with several stops. |

|

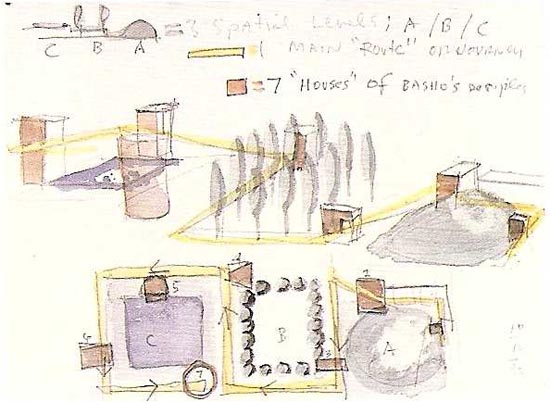

5. House of the Blue Shadow (Meeting centre) We can therefore conclude that -as Bernard Tschumi did at the Parc de la Villette- Steven Holl drew compositional inspiration from English picturesque landscape design and applied it to the block's interior gardens: In fact, all these ideas appear in the conceptual diagram which Holl uses as as a starting point for each of his projects: |

|

6. Steven Holl, Housing in Makuhari. Conceptual diagram It is therefore crucial to highlight the importance Steven Holl gives to diagrams in his architecture, as a resource to generate forms and ideas. |

| “I depend entirely on conceptual diagrams, I consider them to be my secret weapon: they allow me to start from scratch from one project to the next, from one place to the next (…) Finding an initial concept which captures the essence (…) of each project is, for me, the only way to address it, the door through which the new ideas access my architecture” (Kipnis, 1998). |

|

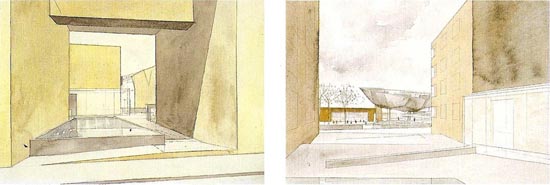

7. Steven Holl, Makuhari. Watercolour studies of the preliminary project Finally, it must be noted that, in addition to their appearance, Holl provided each of the six pavilions with a function. In the end only two of them fulfilled this request: the public meeting room or House of the Blue Shadow -a concrete-built tea pavilion located in the north courtyard- and the House of Nothing -a public observation deck partially covered by a copper-plated pergola located in the Southwest corner of the ensemble-. |

|

|

|

| 8. House of Nothing (observation deck) | 9. Ikebana house |

The cavalier perspective is a special case of axonometric perspectives (specifically, it is an oblique axonometric perspective with a frontal elevation). It makes easy to draw a volume from the lateral views of an object -in architectural drawings, from one of the façades. Therefore, in cavalier perspective representations the elevation view is given priority and shown in real size, as opposed to the plan, which is foreshortened. An analysis of the Makuhari axonometric shows that the main façade (that which Holl considers to represent the project better) is the Western elevation, as it is presented frontally. Furthermore, this cavalier projection is completed using a common angle and reduction factor. Generally, when Steven Holl uses an axonometric perspective to represent his projects, he chooses a cavalier projection -and only opts for military projections in a few of them, like the Berkowitz-Odgis house-. From all this, we can deduce that floor plans are of secondary importance to Holl. In fact, he corroborates this himself, both in writings and interviews. Moreover, he explains that floor plans are only drawn at the final stage from watercolour perspectives and previous work models. |

|

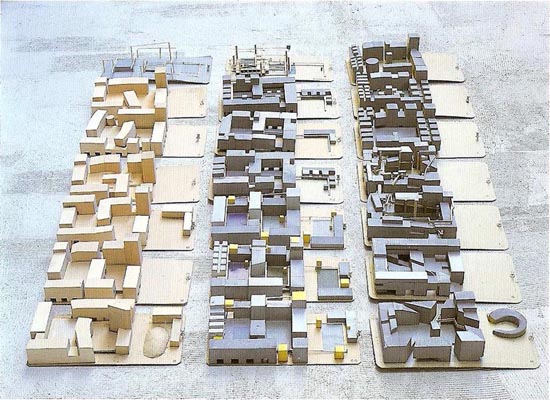

10. Work models for the Makuhari project The Kiasma project in Helsinki is a good example of this. (…) From the beginning of the design process, the museum contained a series of perspectives of spaces, which were separate rooms connected through an emerging perspective. We made some plaster models (…) I later used watercolour perspective drawings, which is something I always do before the floor plans are defined. We often build models from these drawings, and we then try to draw the floor plans, because to me the perspective conditions precede the plans) |

|

|

|

| 11. Steven Holl, Museum of Modern Art, Helsinki. Watercolour | 12. Museum of Modern Art, Helsinki. Photograph |

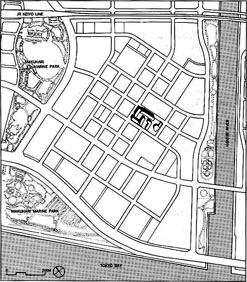

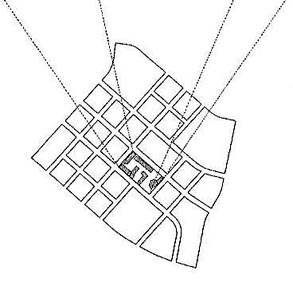

"Architecture is linked to its location. (…) Architecture is not so much an intrusion on the landscape as it is an explanation to it. (…) Ideas that are cropped at the moment when the site is first perceived (…) may become a frame for invention. This mode of invention is concentrated in a relative space as opposed to universal space.” (Holl,1989). The idea of “building the site” -understood as the importance the plot and its surroundings (location, landscape, history, culture,...) have on his projects- is essential to Steven Holl's work. This approach and vision of architecture in which the “place” is not just a physical space is captured in his “Anchoring” and “Intertwining” books, which were written as statements of principles. Considering the representation of the projects, line-drawn exploded axonometric perspectives linked to a site plan are generally used. The Makuhari project (Japan, 1992 – 1996) also belongs to this period although it was published later, in 'Intertwining’. In the book's foreword, Holl reaffirms his belief in “the importance of anchoring architecture to the history of the environment”. However, the only axonometric perspective linked to a site plan that appears throughout the book is that of the Makuhari project, indicating the end of an era and the evolution toward an architecture that is no longer particularly “anchored”. The relationship with the place will continue but it will not be expressed so literally. The curious thing about these “anchored” axonometrics is how they are built. Being cavalier perspectives, the floor plan is foreshortened. To view it without any foreshortening, frontally to the viewer, we have to resort to the site plan to which it is referenced by dotted auxiliary lines linking the axonometric perspective to the site plan, which does not generally have the same orientation as the perspective. This is so to maintain the real orientation of the site plan, which normally corresponds to the geographical North or, as in this case, to important topographic elements (Hanami River and the JR Keiyō railway). |

|

|

13. Site plan of the Makuhari project Returning to the site plan to which the axonometric is linked, we note that only the perimeter of the blocks is drawn, marking the boundary with the street. We have no reference to how the adjacent buildings are. Nor even to whether there are any buildings or not (Makuhari is a new city, located on a dredged terrain by the Tokyo Bay coast). Only the urban weave is represented - that is, the width of the streets and the ground surface of the city blocks. The project's housing blocks are represented by means of a grey hatch. Therefore, this is a location plan that gives us no further information than what we could learn from the axonometric perspective (except for the urban weave). Its only use is to express the idea of “anchoring” to the place graphically. This proves, once again, the close relationship between theory and representation of architecture in Steven Holl's work. In the aforementioned sequence of books, the next to be published was “Parallax” (2000). It is no longer a catalogue of projects, as “Anchoring” and “Intertwining” were, but a series of meditations in which the Makuhari axonometric reappears. However, the site plan to which this axonometric is anchored has been cut out from the image in Steven Holl's website. |

|

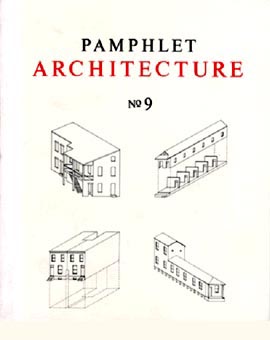

14. Makuhari project axonometric perspective, as it is currently shown on www.stevenholl.com Moreover, in “El Croquis. Steven Holl (1984-2003)” magazine not even the axonometric is included to explain the Makuhari project. (Nor is it used either in the “GA document extra Steven Holl” magazine). This leads us to think, firstly, that Steven Holl has finally given up his “anchoring” period and secondly, that some do not consider the Makuhari axonometric to be particularly representative of the project, perhaps because it is an initial drawing or because it doesn't correspond to what was actually built. Conclusion Axonometric perspectives are not a typical feature of Steven Holl's representation of his projects, being used only in his first period, which begins with the Pamphlet Architecture series in 1977. These publications were to be used mainly as analysis and research documents and therefore demanded essential drawings, based almost exclusively on the impersonal and descriptive nature of axonometric perspectives. |

|

|

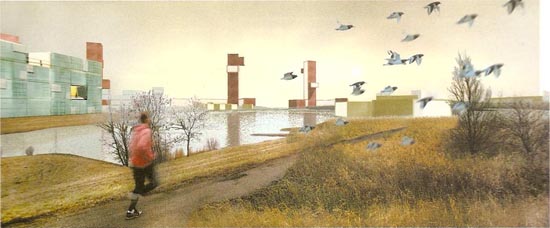

15 and 16. Covers of 'Pamphlet Architecture' publications Later, when his work ceased to be theoretical, axonometrics were still used for a while as part of the representation of his projects, especially to explain the overall volume -always accompanied by watercolour perspectives and models-. With the advent of the computer, however, this form of representation was lost, perhaps also because of a change in attitude or style. In this sense, the Makuhari exploded axonometric perspective and that of Bernard Tschumi for the Chartres business park are very similar. There are two reasons for this similarity. The first is that they serve the same purpose: to explain the project from its essential elements organized by layers. The second is that they correspond to the same period, in which the use of axonometrics is also used by other architects, especially in the case of Deconstructivists like Eisenman or Hejduk, to express processes of analysis and formal exploration. These almost mathematical operations of addition, subtraction, etc. required a distanced form of representation, in which subjectivity and personal views had no place, leading to the use of axonometric perspectives. In most cases, Holl uses cavalier axonometric in which certain faces of the shapes are often shaded to create a chiaroscuro effect without any shadows being cast so as to emphasize the elevations. This is because the floor plans are of secondary importance to him, being drawn only in the final phase of the project from the previous perspective drawings and modelss. In recent years, this form of representing his projects has evolved further, with the use hybrid images composed of combinations (collage), photographs, renderings and his own paintings. |

|

|

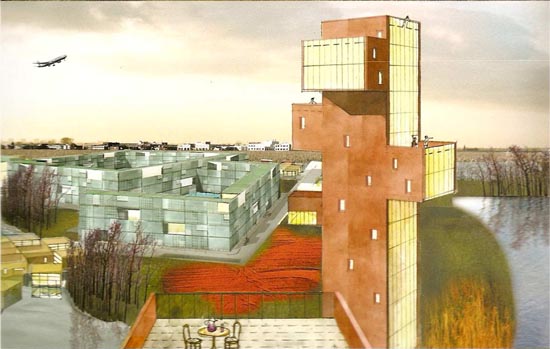

17. Steven Holl, Toolenburg-Zuid Residential complex (competition): a combination of photography, watercolour and rendering Therefore, as a final conclusion we can safely say that the images and the visual approach both to designing and representing projects are very important in Steven Holl's work. |

References in the text:

- Kenneth Frampton, "La obra de Steven Holl: una visión retrospectiva", El Croquis. Steven Holl (1984-2003).

-

Jeffrey Kipnis, "Una conversación con Steven Holl", El Croquis. Steven Holl (1984-2003), 1998.

-

Alejandro Zaera Polo, "Una conversación con Steven Holl", El Croquis. Steven Holl (1984-2003), 1996.

- Steven Holl, "Anclar", Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme, nº 181-182, 1989, pp. 164-165.

Origin of the images:

1 - Steven Holl, Parallax, Basel – Boston - Berlin, Birkhäuser, 2000, p. 223.

2, 6, 7, 10 - El Croquis: Steven Holl 1986 -2003, Madrid, El Croquis Editorial, 2003, p.15, 41, 17, 25.

3 - Steven Holl, Entrelazamientos - Steven Holl: obras y proyectos 1989-1995, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1996, p.117.

4 - El Croquis: Steven Holl 1986 -2003, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid, 2003, p.16.

5, 8, 9 y 14 -

http://www.stevenholl.com/project-detail.php?id=23&worldmap=true

11 y 12 -

Steven Holl, Steven Holl: Luminosity / Porosity, Tokyo, Toto,2006, p. 201.

13 -

GA document extra 06 Steven Holl, Tokyo, A.D.A., 1983, p.49.

15 -

http://www.chroniclebooks.com/images/items/9780910/9780910413169/9780910413169_large.jpg

16 -

http://www.stevenholl.com/books-detail.php?id=43

17 - El Croquis: Steven Holl Architects 2004 -2008, El Croquis Editorial, Madrid, 2008, p. 455.

Recommended bibliography:

- GA document extra 06 Steven Holl, Edita A.D.A., Tokyo, 1983

- Steven Holl, Anchoring: selected projects 1975-1988, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 1989

- Steven Holl, Entrelazamientos - Steven Holl: obras y proyectos 1989-1995, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1996.

- Steven Holl, Parallax, Basel - Boston - Berlin, Birkhäuser, 2000

- El Croquis: Steven Holl 1986 -2003, Madrid, El Croquis Editorial, 2003

- El Croquis: Steven Holl Architects 2004 -2008, Madrid, El Croquis Editorial, 2008

© of the text Teresa Díez Blanco

Teresa Díez Blanco is a professor of Interior Design at the Superior School of Design and Plastic Arts (Escola Superior de Disseny i Arts Plàstiques - ESDAP).

© by Pol Foreman and Antonio Millán-Gómez: English translation

Antonio Millán-Gómez is professor at the Superior Technical Architecture School of Vallès (Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura del Vallès), UPC

>> Back to the top of the page

>> Back to Dibujos Ejemplares de Arquitectura