Jacques Lemercier's drawing of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

|

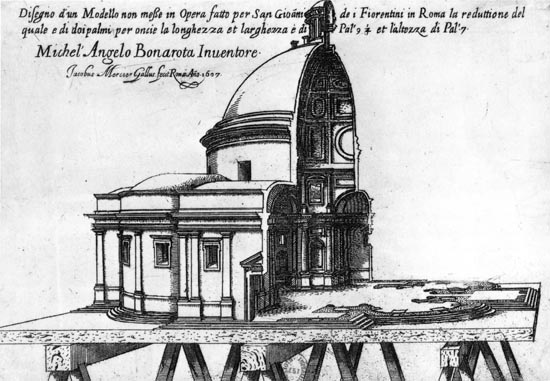

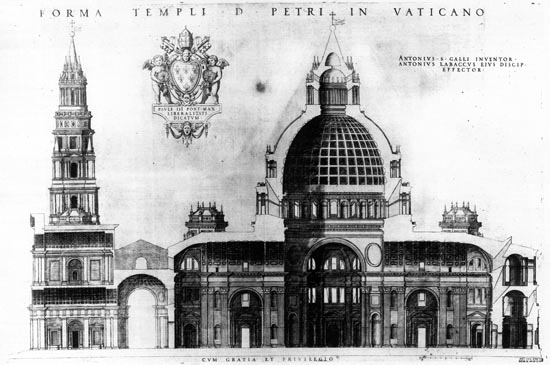

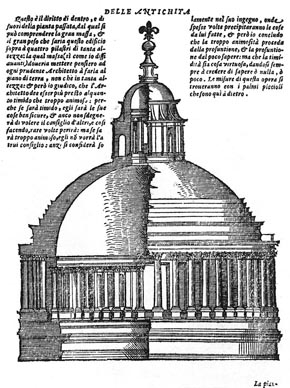

1. J. Lemercier, Maqueta del proyecto de Miguel Ángel para San Giovanni dei Fiorentini In 1607 Jacques Lemercier drew and etched the wooden model of Michelangelo's design for the church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini in Rome (fig. 1)1. Contrary to what he usually did, Lemercier decided not to draw the building represented by the model, but the model itself, placing it on a wooden table with three trestles. He also inserted the measurements and reduced scale in the title of the etching: 'Drawing of a Model not implemented but made for San Giovanni dei Fiorentini in Rome; the reduced scale is two palms per inch for the length while the width is Pal' 9 ¼ and the height is Pal' 7'. Under the title he added information about the author of the design, 'Michel' Angelo Bonarota Inventor' and the author of the etching: 'Jacobus Mercier Gallus fecit Romae Año 1607'. Lemercier was as accurate in the title as he was in the drawing: the right trestle is smaller and its horizontal transverse section is lower than the others. Clearly Lemercier was not a 'conventional' architect, but why then did he lavish his interest in the building onto the model and onto the tool he used to represent it, thereby transforming the element of mediation into the protagonist? Maybe Lemercier wanted to avoid proposing the idea of a real building when in fact it was only a model. Undoubtedly he admired Michelangelo since he used several of the latter's architectural solutions2 and kept a portrait of Michelangelo in his study along with small copies of Moses and the Pietà. Perhaps he wanted to emphasise the fact that Michelangelo's design had been abandoned in favour of the one by Giacomo della Porta.3. In this case his behaviour is reminiscent of Antonio Labacco's decision to publish the drawings of the model of St. Peter's (fig. 2)4. |

|

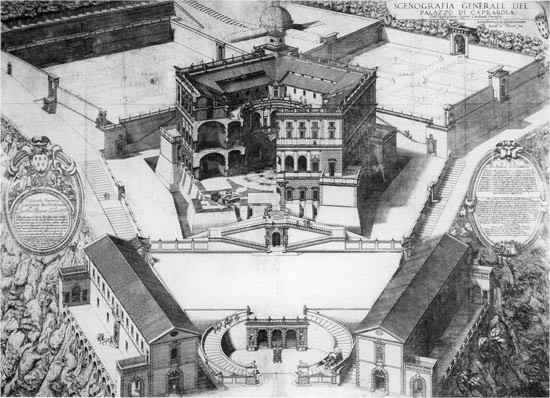

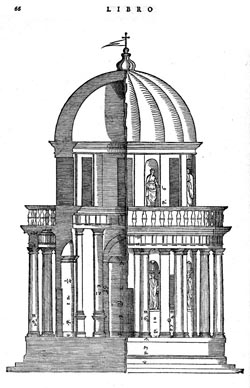

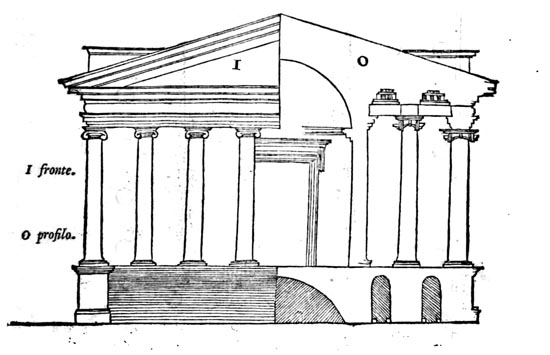

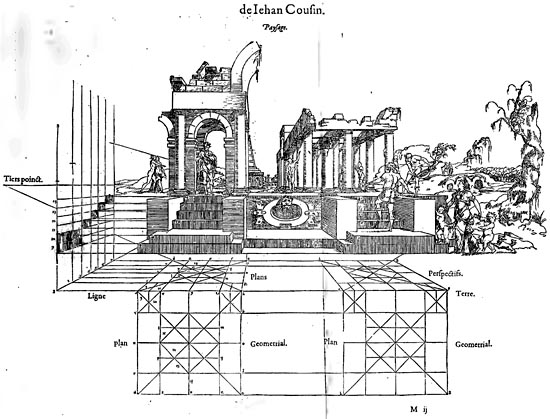

2. A. Labacco, Sección de la maqueta de Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane para San Pietro in Vaticano According to Vasari, Labacco wanted to illustrate Sangallo's skill and make every man aware of the work of that Architect; this could have been the reason behind Lemercier's choice. In both cases the model still existed and could be admired and studied 'by everyone'; publishing the etching, however, was a way to ensure that it was not forgotten and let everyone in Rome become familiar with the work. Jacques Lemercier in Rome Lemercier was then 22 years old and was living in Rome to follow an apprenticeship that was meant to last until late 1611 or early 1612. He came from a family of master-builders and his father, Nicholas Lemercier (1541-1637), was an important figure in the Vexin region in France. In fact he was considered as "un des braves architects de ce temps", mentioned as a "maitre masson du roy pour la chastellenie de Pontoise" or "géomètre du roy" or as "architecte des Bâtiments du roi", "architecte des Bâtiments de la reine" or, more frequently, as "mâitre maçon et architecte de la reine". Based on these premises, it's likely that Lemercier learnt to draw at an early age and, given the drawings he made in Rome; it's also likely he was familiar with the book of perspective by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, the one by Jean Cousinor, perhaps, the book by Jean Pélerin (Le Viator). The meticulous training that Nicholas Lemercier could give his son meant that even before going to Rome the young man was familiar with Jean Martin's translation of Vitruvius' De Architectura or the treatise by Philibert de l'Orme. It's also possible that the latter was Lemercier's referent during his training and journey to Rome5 and that he had seen the drawings by Du Cercea. and, possibly, the ones by Étienne Dupérac. His journey to Rome at a time when this kind of journey was not customary in France indicates that he was already well trained and wanted to improve his skills. We do not know the exact dates of Lemercier's journey to Rome, nor how long he stayed in the city. It's very likely he travelled with Charles de Neufville de Villeroy, Marquis of Alincourt and Ambassador to Rome from 1605 to 1608 (Lemercier's father had worked for Charles in Pontoise). Correspondence between the dates of the journey and Lemercier's activities in Rome are documented, making it highly probable that he travelled with the Marquis in 1605 and that the latter protected him and introduced him into the Roman milieu. Only the four etchings testify to his time in the city. The first is the one mentioned earlier (1607), but he also executed three more: Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola dated 1608 (fig. 3), the statue of Henry IV currently housed in the Loggia of Blessings in St. John Lateran (1608) and finally the biers for Henry IV's funeral, again in St. John Lateran (1610). |

|

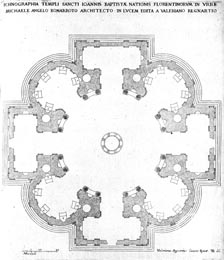

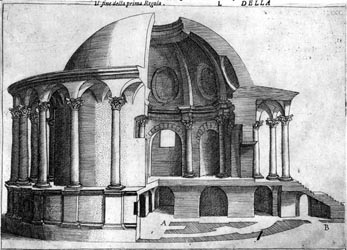

3. J. Lemercier, Palazzo Farnese di Caprarola The dates of these etchings are linked to the Marquis' return from Paris and his attempts to obtain new patronages from King Henry IV, Queen Maria de' Medici (for whom his father was "master-builder and architect") or from Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, owner of Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola. The names on the etchings are proof of his introduction into the Roman milieu: "Jacobus Mercier Gallus" for St. John Lateran, "Iacomo Le Mercier" for Palazzo Farnese, a concise "J. Le Mercier" for the statue of Henry IV, and "the French Mercier" for the bier. The names in all the texts are in Italian and Latin, except the third which is in French. Finally, A "French Giacomo" is present in the Accademia di San Luca between 1607 and 1611; it could correspond to Lemercier, but we cannot be sure it is the same Frenchman. The model and its representation The wooden model was a copy of the first terracotta model made by Tiberio Calcagni in 1560 based on the instructions he received from Michelangelo who, then aged 93, was far too busy with the works for St. Peter's and didn't have enough energy to tackle this project all by himself. According to Vasari, it was the admiration shown by the city of Florence for the model that encouraged Michelangelo to make a wooden model some time later. During that period it was normal for a model to be made in two parts so that it could be opened to let people see inside; Lemercier depicts it open, eliminating one of the two parts. The model was kept in a room next to the church until 1720 when it was destroyed during a fire. Some years later another etching of the model was made, an etching we could call traditional. It's worth taking this model into consideration. In actual fact there were two etchings: one shows the juxtaposition of half of the elevation and half of the section (fig. 4). The other portrays the plan of the church (fig. 5). They were both part of the Praecipua urbis Romanae templa6 by Valeriano Regnart with drawings by Domenico Parasacchi. |

|

|

|

| 4. D. Parasacchi y V. Regnart, Alzado y sección del proyecto de Miguel Ángel para San Giovanni dei Fiorentini. | 5. D. Parasacchi y V. Regnart, Planta del proyecto de Miguel Ángel para San Giovanni dei Fiorentini. |

|

|

|

|

| 6. S. Serlio, Sección y alzado del proyecto de Bramante para San Pietro. | 7. A. Palladio, Sección y alzado del Tempietto de Bramante. |

One example illustrating the difficulties inherent in differentiating and making people understand Parasacchi's composition is an illustration in The Ten Books of Architecture by M. Vitruvius with comments by Daniele Barbaro (fig. 8). The line is straight, so in order not to confuse the reader, the draughtsman adds two letters to differentiate between the parts: I (façade) and O (section). |

|

8. A. Palladio (forse), Alzato e sezione de un tempio d'aspetto diptero. Lemercier did not use this kind of representation,very similar to what was recommended by Alberti and Rafael and adopted by Labacco for the model of St. Peter's. Instead he opted for a perspective based on what was suggested by de l'Orme in his treatise.7 There was a precedent to the image he created: a drawing Labacco himself had published in his own book (fig. 9). In this drawing the plan, elevation and section are jointly portrayed in a single perspective image and the cuts are created using plane sections. It's possible that Labacco's book sparked Lemercier's interest either due to the excellent illustrations, or to the fact Labacco had drawn the model of St. Peter's or, perhaps, his etchings. This particular composition could have been inspired by a drawing by Vignola, later to be included in The two rules of practical perspective (fig. 10)8. |

|

|

|

| 9. A. Labacco, Templo dórico cercano al Theatro di Marcello. | 10. Vignola y E. Danti, Templo de Portumno. |

The symbolic value of the model It's likely that Lemercier considered the model a characteristic element of Italian architecture. In fact Italian architects were the first to use models, not only as a design tool to illustrate the volume or convince a client, but also as a way to present a design either during a competition or as a guiding principle during construction. TheItalians introduced the use of models in France inthe early sixteenth century and the French, for example De l'Orme, began to use them after returning from Italy. Alberti provided theoretical assistance in his De Re ædificatoria believing the model to be not only a necessary tool to study a design, but also a way to complement the drawing and replace a perspective. In fact, Ackerman maintains that in the Renaissance "drawings were not the chief means of communication between architects and builders", because models made it possible to avoid drawing the elevations of the buildings and allowed builders to work using the plans and the specific forms of the models. In France De l'Orme dedicated two chapters of Le premier tome de l'architecture to models, stating that "il y a chose tant nécessaire que un bon modelle". Starting in 1540 the use of models became more widespread and by the last quarter of the sixteenth century it had become routine. The models were made of wood, cardboard or terracotta and in some cases were sectioned so that it was possible to look inside. At that time the model of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini was already a tangible artefact replacing the real building. This is why Parasacchi represented the building without making any reference to the wooden model, because the latter was only a tool, like a drawing or etching. But Lemercier could not follow suit because, all things considered, the model was not a complete or finished objecs but merely the starting point for a work that history had decided not to pursue. It veiled a mystery regarding what the work would have looked like, a mystery comparable to the mystery of the ruins of ancient Rome where imagination had to complete what is hidden by reality. Conclusions However the model represented Michelangelo's design and Lemercier could see it contained the "furore" of his "initial ideas", the energy not yet lost during construction: the importance of the "unfinished" mentioned by Vasari or, perhaps, what was enclosed in incomplete works according to Pliny: "the last works of certain artists [...] are admired more than if they had been completed: in fact, they reveal the lines of the missing part of the design and therefore capture the thoughts of the artist and the regret that the hand of the artist was abruptly halted while in full activity". On the other hand, his training was based on what he had read in de l'Orme and perhaps Michel de Montaigne, and what he had seen in Cousin, De Cerceau and Dupérac. Perhaps this is why he portrayed a simple, bare model, not "fardé, ou, si voulez, enrichy de painture, ou doré d'or moulu, ou illustré de colours"; this is obvious in the way in which he renders the section of the wood. Clearly and in a straightforward manner. He completes the drawing by adding the table and the trestles, revealing that it was in fact a model, and by including the measurements and scale in the title. By doing so Lemercier follows De l'Orme's rule, but also the comments made by Michel de Montaigne early on in his Saggi: "I wish that I be considered here in my manner of being simple, natural and customary, without affectation or artifice". In fact, the way in which he draws the trestles betrays the influence exerted by several etchings by Cousin (fig. 11), Du Cerceau (fig. 12) or Dupérac (fig. 13), in which the surroundingsare included in the representation of buildings. |

|

11. J. Cousin, Paysage. Perhaps this is the kind of "natural philosophy" recommended to architects by De l'Orme and defended by Montaigne: an activity that seeks "only to see how and why everything happens, to observe the life of other men in order to judge their lives and then fine-tune one's own". |

|

Notes:

Origin of the images: 1 - Frommel, Sabine, and Tassin, Raphaël. 2015. Les maquettes d'architecture : fonction et évolution d'un instrument de conception et de réalisation. Paris, Roma: Picard e Campisano,. 325 p., p. 203.

|

>> Back to the top of the page

>> Back to Dibujos Ejemplares de Arquitectura