PHILIP JAMES DE LOUTHERBOURG, Avalanche in the Alps

Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

|

Philip James de Loutherbourg, An avalanche in the Alps, 1803 Loutherbourg‘ painting (1740-1812) portrays the moment when an avalanche startles some people walking along a pass in the Alps. Snow falls violently, destroying the bridge these people were about to cross. One of them is praying, asking God for help, while another one is running to save his life. A third person stares -entranced in disbelief- the avalanche; he is paralyzed, impressed and does not seem scared at all. He even seems dazzled by that nature’s spectacle that he is observing, which overwhelms and immobilizes him. This is a representation of the idea of the sublime, as it was understood in 18th century literary and artistic circles. The concept belonged to the baroque period, but it actually was identified as a concept with specific character during Neoclassicism and especially during Romanticism. |

|

Another image portraying the sublime is The pass of St.Gotthard, by William Turner (1808). | |

|

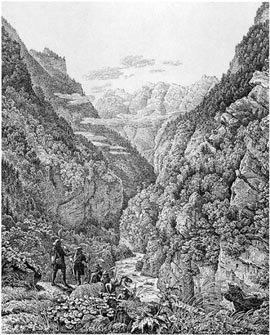

The Lueg Pass, near Salzburg (1811) is one of Schinkel’s engravings, evoking the feeling of abyss and vertigo. |

The sublime was related In the XVIII century to qualities such as darkness, grandeur, magnificence and, subsequently, to feelings such as fear, astonishment, or respect. Therefore, it was not only related to grandeur, but to a certain feeling of pain and danger, as well: whatever is suitable to trigger the ideas of pain and danger, that is, whatever is somehow terrible or linked to terrible objects or behaves in a similar fashion to terror is a source of the sublime; in other words it provokes the strongest emotion that the mind can feel. Obviously, when either pain or danger is too strong there is no pleasure, but from a distance they may be objects of satisfaction. Therefore, the sublime implies an ambiguous complacency; it is a certain delicious horror. The sublime proves man how small he is compared to nature. While in paintings picturesque nature is a cozy and propitious atmosphere that makes the individual develop social feelings, in the sublime nature is a hostile environment that makes the individual aware of his own individuality, his solitude. Whereas the picturesque is the poetry of the relative, the sublime is the poetry of the absolute. The success of Burke’s book proves the importance that the poetry of the sublime had in England, success later extended to Germany, France, and Italy. It is interesting that the issue of the irrational arouse as a problem of existence during the century of reason. To Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Judgment, the picturesque and the sublime are two attitudes of man facing reality: they reflect the relationship between the individual and the community, which will be present in the artistic production during the 19th and 20th centuries. Possibly, the architect who has identified the most with this poetry of the sublime may be Etienne-Louis Boullée. |

|

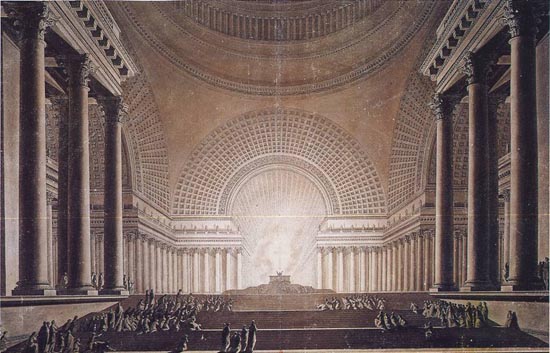

| This is his basilica, |

|

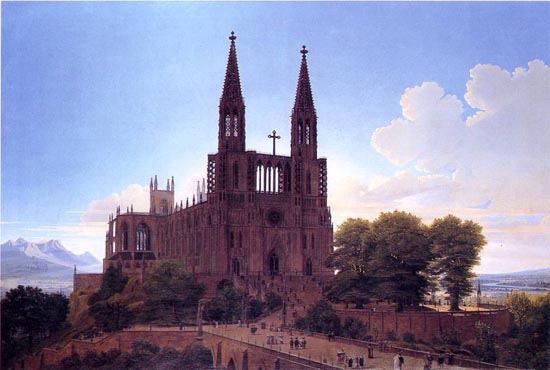

This is the cenotaph for Newton. The following are some Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s images, |

|

Here the sublime arises from the contrast between the highly illuminated background and the dark cathedral as a result of back lighting. For a while (before 1815) Schinkel worked as a painter and stage designer and developed a special talent for capturing the pictorial relationships between the building and the environment. |

|

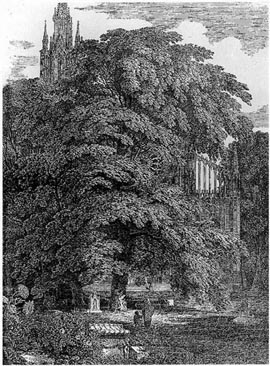

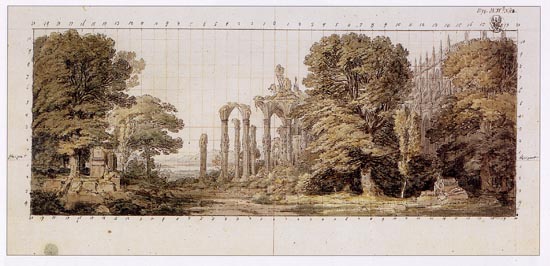

In this image, vegetation is hiding the cathedral. | |

|

Another drawing by Schinkel, this time the ruins of a building are taken over by vegetation. They are defeated by nature.

|

Recommended bibliography:

- Edmund Burke, A Philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful, 1757.

- Walter John Hipple, Jr., en The beautiful,

the Sublime & the Picturesque in Eighteenth-Century British Aesthetic

Theory, Carbondale, The Southern Illinois University Press, 1957.

- Rosario Assunto, Stagioni e ragioni nell'estetica del Seteccento,

Milan, V. Mursia, 1967.

© of the texts Francisco Martínez Mindeguía.

© of the English translation Ruth Costa Alonso and Antonio Millán-Gómez.

Antonio Millán-Gómez is professor at the Superior Technical Architecture School of Vallès (Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura del Vallès), UPC.

>> Back to the top of the page

>> Back to Dibujos Ejemplares de Arquitectura