GEORGIA O'KEEFFE, American Radiator Building, 1924

Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

|

|

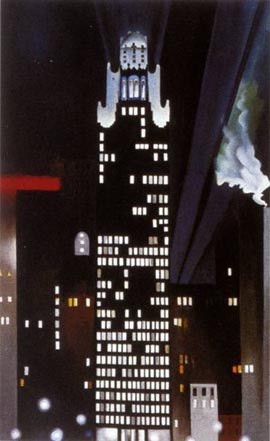

Georgia 0'Keeffe, American Radiator Building, 1927 This oil painting by Georgia 0'Keeffe (1887-1986) is a night view of the American Radiator Building in Nueva York, designed by the architects Raymond Hood and André Fouilhoux, in 1924. It belongs to the series of New York’s landscapes that she painted between 1925 and 1930, insisting on the theme of skyscrapers, a North American invention that attracted interest and admiration worldwide. With straightforward and basic resources, O’Keefe managed to portray in these series what some had considered being New York’s very image. In this image, two features are superimposed: skyscrapers and night lightening. These are different and independent things, but they became altogether the image of modern city at the turn of 20th century, the same that European capitals intended to achieve. |

|

|

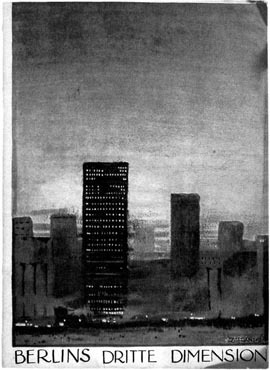

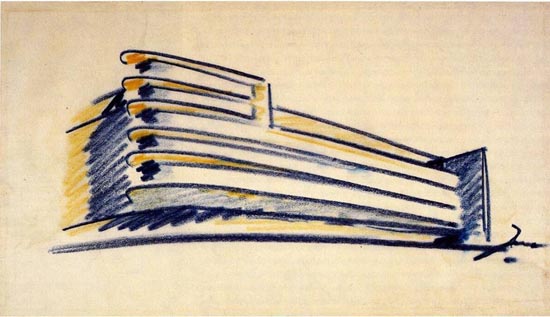

Let us use as an example, this one of Kurt Szafranski ‘s drawing,entitled Berlins dritte Dimension (Berlin’s vertical dimension), originally the cover of the Berliner Morgenpost brochure, which in 1912 gathered the opinions of important people from Berlin, such as Walter Rathenau, AEG’s manager, or Peter Behrens. The opinions were about the skyscrapers, but curiously enough, the drawing portrays a night image of the city. The invention of artificial lighting, and its use for lighting cities, created the night image of the city, the image of a new city which could be invented. Artificial lighting would change the city’s image, and it even managed to create a new city and the possibility of its design. We can compare 0'Keeffe’s image with the image of his model. |

|

|

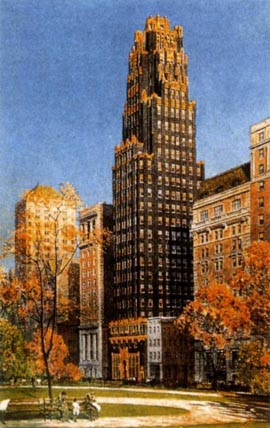

This is the daytime image of the skyscraper in 1924, according to Birch B. Long. | |

|

And this is the image of the same skyscraper during the night. The upper part of the buildings, resembling a series of steps, was used to turn these towers into light torches. |

|

|

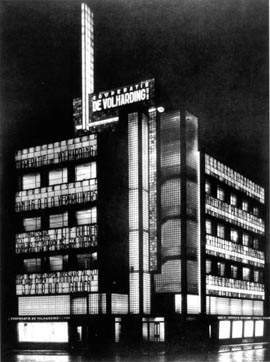

This is the Volharding Building, designed by the architects Jan Willem Eduard Buijs and Joan B. Lürsen, in The Hague, in 1928. | |

|

This is the store Elektrowirtschaft, lit outdoors at night, in Zielona Góra, Polond, 1928. Night was the new blank sheet of paper in which light was a pencil as well as its color. Everything seemed possible. The artist-technician would control what would be seen, and how it would be seen. Thus, night became an art object. |

|

|

This is a photo composition by Fritz Lang, titled Times Square, dated in 1924. In it, he uses double exposure.

|

|

|

This is the nighttime image of “the new Babel’s tower,” from the movie Metropolis, by Fritz Lang (1927). In 1926, the term Architecture of light was already popular in Germany (Lichtarchitektur) although Raymon Hood finally coined it in 1930. Architects such as Erich Mendelsohn, Bruno Taut, or Mies van der Rohe began taking into account the late-time appearance of buildings. And painters such as Femand Léger or Lászió Moholy-Nagy used nocturne images of cities in their paintings. It was an abstraction that provided a new image of the building. |

|

|

|

| This is Peterdorff’s warehouse in Bresiau, by Erich Mendelsohn, (1928). Architects began thinking in the night image of the building. Night vision was something that the architect was capable of creating, and controlling, despite the surrounding conditions: a nocturnal image which could be identified with that of the project. |

|

The following are two images of Van Nelle Tobacco Company Factory, designed by the architect Johannes Andreas Brinkman (with Leendert Cornelis van der Vlugt and Mart Stam), in Rotterdam, 1926-29. |

|

|

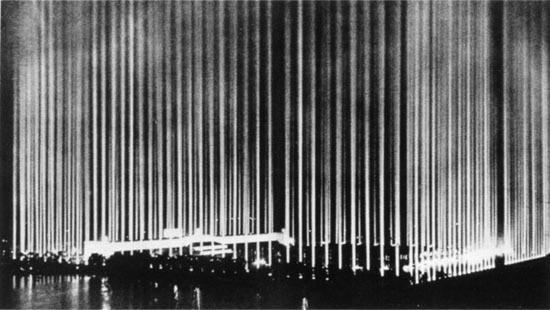

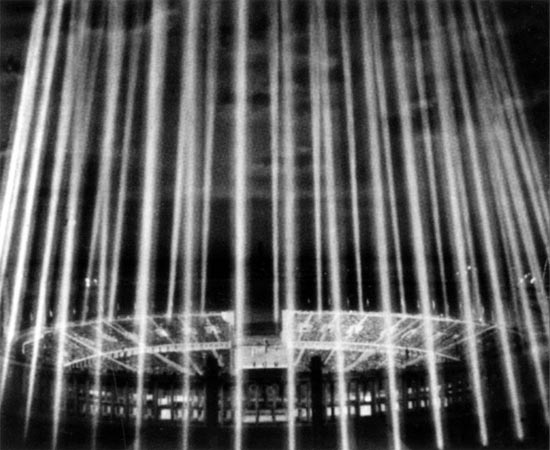

| From a political point of view, the night would allow hiding whatever unpleasant features the city could have and show only the dazzling ones. The following is an image of a “cathedral of light,” which the architect Albert Speer “built” for the oath ceremony of political leaders in the Field Zeppelin in Nuremberg, in 1936. |

|

|

Since 1933, when the German National Socialism regime gained access to power, Speer experimented with powerful lights in nocturne political events, taking advantage of the propagandist opportunities they offered. The following image shows the spectacle that he prepared for the closing ceremony at the Olympic Games in Berlin, in 1936. |

|

|

This is another “cathedral of light,” by Albert Speer in Berlin, in 1939, arranged as the stage for the nocturne parade to celebrate Hitler’s return from Prague. | |

|

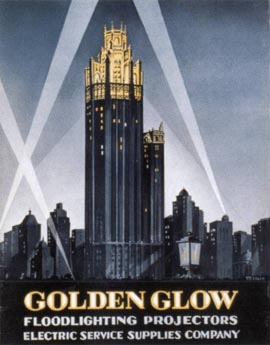

Big commercial companies saw the possibility to create or improve their corporation image with light, and buildings begun to be lit. The image is the cover of a sales brochure of the company Golden Glow, in 1932, and the building is the Chicago Tribune Tower, in Chicago, designed by the architects Raymond Hood and John Mead Howells, in 1929. | |

|

Front page of Illumination News, 1932. | |

|

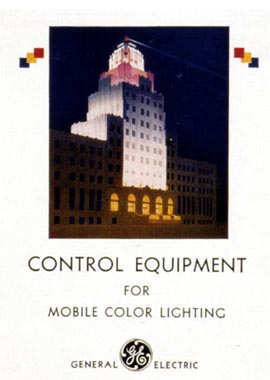

General Electric Company’s brochure, 1931. It shows an image of the Staley Building in Decatur, Illinois, designed by the architects Aschauer & Waggoner, 1930. | |

|

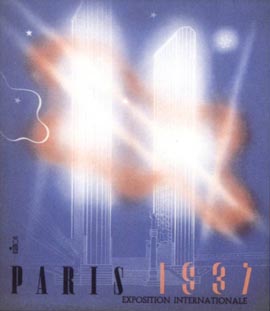

Poster of the International Exposition of Arts and Techniques in Modern Life. Paris, 1937. It shows its fully lit access towers. |

Recommended bibliography:

- Anna C. Chave, "Who Will Paint New York?", American Art,

vol. 5, nº 1/2, 1991, pp. 87-107.

- Regina Stephan, Eric Mendelsohn. Architect

1887-1953, The Monacelli Press, 1999.

- Dietrich Neumann, Architectura of the Night.

The Illuminated Building, Munich, Berlín, Londres y Nueva

York, Prestel, 2002.

© by text Francisco Martínez Mindeguía.

© by English translation Ruth Costa Alonso and Antonio Millán-Gómez.

Antonio Millán-Gómez is professor at the Superior Technical Architecture School of Vallès (Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura del Vallès), UPC.

>> Back to the top of the page

>> Back to Dibujos Ejemplares de Arquitectura