MICHAEL GANDY, The Bank of England in ruins, 1830

Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

|

|

|

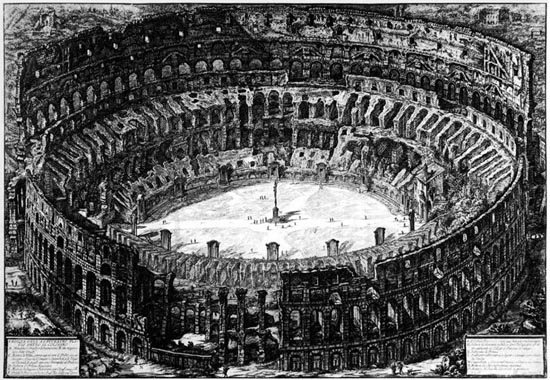

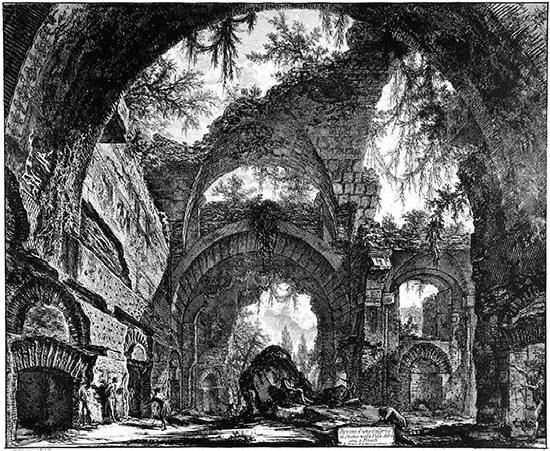

Drawing by Michael Gandy, The Bank of England in ruins, 1830 In 1830, at the peak of his career, John Soane made an exhibition of his work in the Royal Academy of London. For it, he put Gandy in charge of a perspective of the Bank of England in ruins. This was possibly his most important and famous work. In 1788, Soane had been appointed architect and surveyor to the Bank of England, with support of the Prime Minister William Pitt. The perspective shows half of the main facade and the plan, in which its more representative spaces can be distinguished. If you know the building, each one of the actions that generated the final form can be seen, the sum of parts with their own symmetries. Surprisingly, Soane and Gandy represented the building in ruins, like it was a antique building from the antiquity. In fact, the drawing recalls the appearance of other known drawings of the ruins of the Forum of Rome and the Villa Adriana, in Tivoli. The ground outside the building has sunk and has exposed the foundations, an image that can remind of the back view of the Roman Palatine. Curiously, despite the ruin, there is no wreckage and the building glows in such way that it prevents us from seeing the surroundings. Ruins of classical buildings are accumulated all around it, as in Piranesi’s engravings. For example the following one, of the Roman Coliseum. |

|

Thus, the drawing displays the Bank of England as if it were an antique, with the aura and the mystery that it implies. This suggests that even if time passes and the building is seen in ruins, it can still be perceived as something admirable. In Rome and Greece the ruin was the preserved testimony of the ancient splendour. In England, which did not have this past, the ruin was used as an image, with literary content, and it joined the poetics of the picturesque. The ruin suggests the relentless pass of time and the nostalgia of the past. As with the gardens, an extensive bibliography on the ruins was created in England. Among it, a text by Thomas Whately, included in Observations on Modern Gardening, 1770, in which he said: all ruin arouses curiosity about the ancient state of the building and draws the attention on the current use... (by this, he refers to the change of use), to achieve these effects, the ruin need not be real, although the artificial ones can only reach a certain level. The feelings do not have the same strength even if of the same nature and although it does not lead to the memory of events, it can stimulate the imagination... The value we attach to the monument is not the fact itself, but the relations that can be stimulated in our imagination. This is important because it refers to a variety of meanings and contents, mostly subjective, they manage to suggest. Before he, William Shenstone, in Unconnected Thoughts on Gardening, 1764, had said: a ruin ...may not represent anything new for us, neither majestic nor beautiful, but it provides the pleasurable melancholy that comes from reflecting on the decayed magnificence. The ruins had an enormous fascination. Destroyed by time and history, they were a combination of human work and organic nature: they allowed reconstructing imaginatively the original space; they were documents of the past and by their associations they could induce emotional states. They also had a great evocative power. In 1709, the architect and playwright John Vanbrugh (1664-1726) had said that the ruins moved to the most lively and pleasant thoughts on the people who inhabited [the places], the notable events that occurred there or on the special occasions in which they erected: the buildings can evoke history stronger than books and can be part of the landscape (see: B. Dobrée and C. Webs, The Complete Works of Sir John Vanbrugh, 1928). In 1747, the writer Thomas Warton (in The Pleasures of Melancholy) had linked the ruins to the feeling of what was sublime. And in 1699 another writer, Thomas Burnet (in Telluris Theoria Sacra, 1699), wrote that in the contemplation of ruins the mind is stimulated to sublime feelings and thoughts. And also that through the ancient temples of the Romans, their crumbling amphitheatres, we know the greatness of these people. The ruin may also be the starting point of a speech. Downloaded from negative evaluations of the old, the ruin is something that still retains an echo of a past splendour or activity that it had. The ruin is no good for practical purposes and is art alone... Two years later, in 1832, Michael Gandy repeated the drawing with an emblematic part of the Bank, the Rotunda, built between 1794 and 1796. |

|

This is the drawing that Gandy made in 1798, when it was already built. Gandy showed a scarcely decorated and full of light interior. What both are interested interest in representing is the dramatic quality of the light which, thanks to the bareness inside, becomes more radical and expressive, cleaner and more visible...in order to feel the thrill of a space that does not need additional attributes (Moleón, p.144). In the drawing he did in 1832, the Rotonda in shown in ruins. |

|

Here the ruin seems to suggest the melancholy that Shenstone and Whately were talking about. In this situation it is possible to compare the building with the monuments designed by Piranesi, of the Roman antiquity. |

|

|

Soane and Gandy never got to lose the influence the imprint of their stay in Rome had on them. |

Recommended bibliography

- Margaret and Richardson y MaryAnne Stevens, John

Soane Architect, Londres, Royal Academie of Arts, 1999

- Pedro Moleón, John Soane (1753-1837)

y la arquitectua de la razón poética, Madrid, Mairea,

2001

- Brian Luckacher, Joseph Gandy. An Architectural

Visionary in Georgian England, Londers, Thames&Hudson, 2006

© of the text Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

© of the English translation Monica Stoinea

>> Back to the top of the page

>> Back to Dibujos Ejemplares de Arquitectura