THE GRAND TOUR AND THE SOCIETY OF DILETTANTI

Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

|

|

|

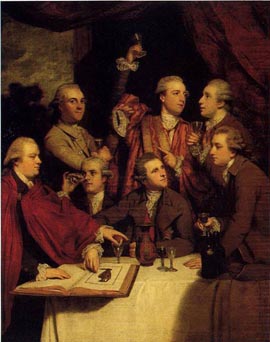

Since 1604, when England and Spain ceased there war hostilities, after the restoration of the Stuart dynasty and especially after the "Glorious Revolution" of 1668, which gave the country greater political stability, it became fashionable among the young aristocrats and wealthy families to finish their studies with a trip to Italy. This is what is known as the Grand Tour, which reached the highest intensity in the second half of the eighteenth century, decreasing after 1796, when France invaded Italy and the Venetian Republic fell into the hands of Austria. Initially, these trips were quite unpopular among English families, mostly because they entailed going to a Catholic country where young people could be tempted by forbidden pleasures and amusements. Other drawbacks were the organization of the trip and the high cost. The trip was normally made with a paid companion. In some cases, not just one companion, but a retinue. Perhaps the extreme case was that of John Cecil, Count of Exeter (1648-1700), who, in 1679, made his first trip accompanied by his wife, his 5 year old son, two guards, a chaplain, 5 women (?), 14 waitresses and 30 horses. The second trip was made only with two companions, a chaplain, an administrator and 4 waiters. Another case was that of Richard Boyle, Count of Burlington, who travelled with a Huguenot pastor, a painter, 4 drivers, a lackey, a waiter, a cook, an accountant, 4 slaves, a preceptor, a physician and 3 musicians. These trips were expensive, since, besides the displacement, they had to pay accommodation, parties and purchases of books and works of art. Gradually, these trips were extended to other social classes Amidst this environment, there was an important event in London: a group of about 40 young men, rich and aristocrats, founded the Society of Dilettanti in 1734. It was a kind of club that aimed to promote the “Greek taste and Roman spirit”. To this end, they subsidized expeditions to Greece and Italy, for themselves or others, architects, archaeologists and scholars. |

|

|

|

This group was to fund some of the most important expeditions for the knowledge of the architecture in Greece and Asia Minor. The most famous ones are those of Robert Wood in 1750, and James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, in 1748-1755. Robert Wood’s expedition to Greece, Asia Minor and Syria was led by James Dawkins (? -1757, a wealthy gentleman) and John Bouverie (1722-1750, amateur archaeologist). Robert Wood was a travel "guide", as he had been in Constantinople, several Aegean islands, Egypt and some cities in Syria and Mesopotamia. Wood was an erudite in classical themes, with sensitivity to capture the characteristics of a place, and a subtle understanding of natural beauties. For this reason Dawkins and Bouverie invited him to accompany them. Along with them went the architect, landscape architect and artist Giovanni Battista (Torquilio) Borra (1712-1786), as well. Wood and Borra drew the ruins of the cities of Palmyra (Syria) and Baalbeck (Lebanon), and published the drawings in two books, The Ruins of Palmyra in 1753, and The Ruins of Baalbeck in 1757. |

|

|

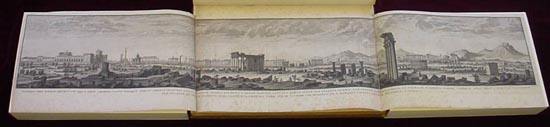

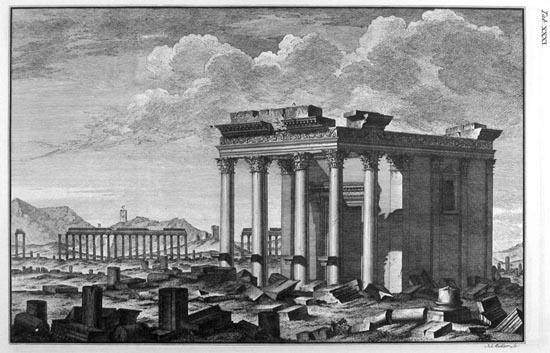

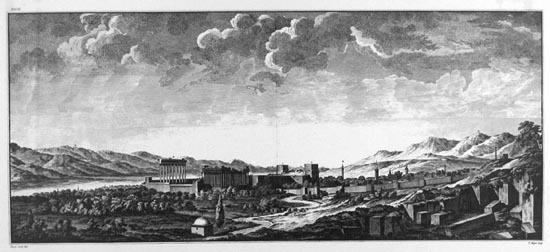

Compared with Desgodets’ work, the building here is no longer considered as an autonomous monument, independent from the environment where it is located. Wood starts from the image of the city (the desolation, the ruin...), in which he represents the situation of each piece related to the whole and the correlation each has with the other pieces. This appears as a reflex of certain sensitivity for landscape, coming from his English culture. After this panoramic view and a situation plan, the book shows each building, starting with a perspective and then plans, sections, elevations, details,... |

|

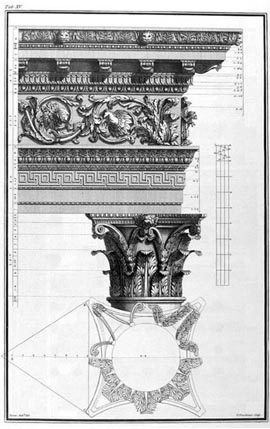

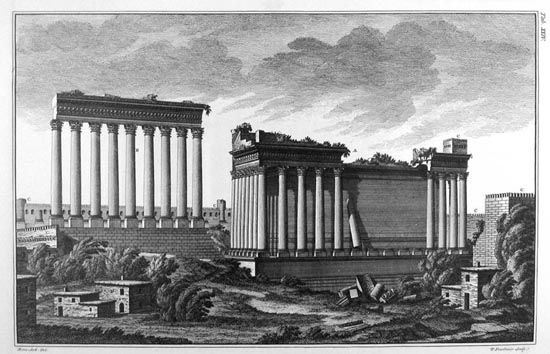

This is one of the studied buildings. First a perspective , |

|

|

|

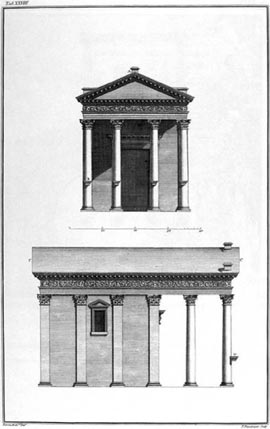

The book of the ruins of Baalbeck has the same structure, begins with a perspective, |

|

Followed by the situation plan, |

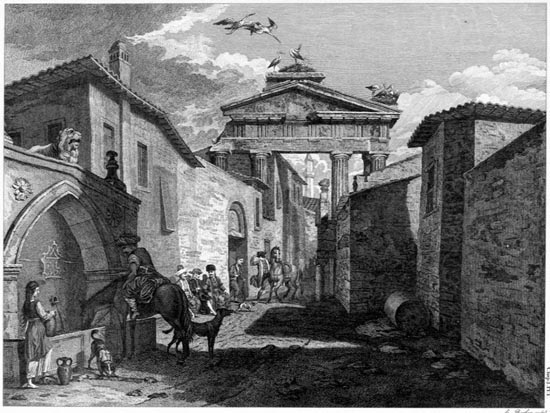

Before each building, a view of the environment, |

|

And then the plans, elevations, sections,... |

|

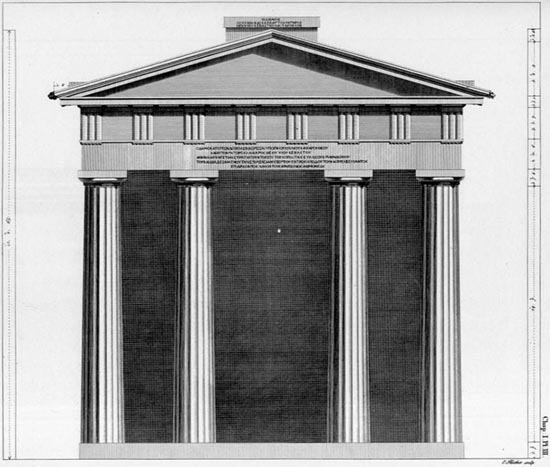

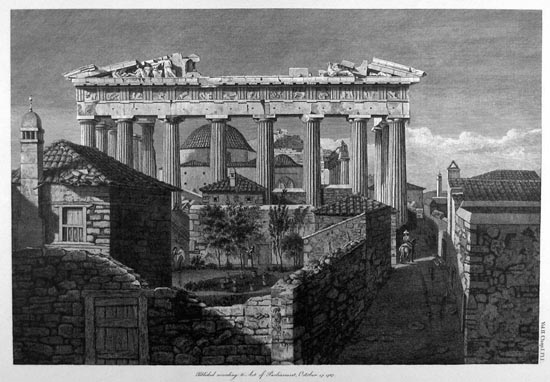

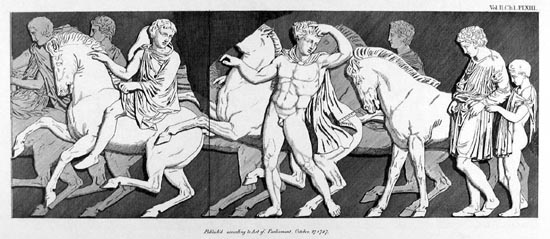

The drawings were published in four volumes of engravings, in 1762 and 1812, entitled The Antiquity of Athens. This book's structure is similar to Wood’s. Every building starts with a view of the ambiance, |

|

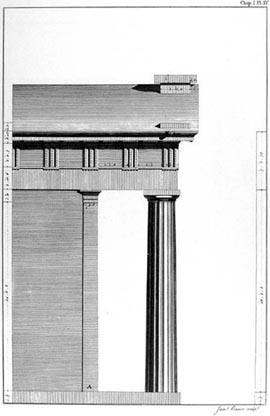

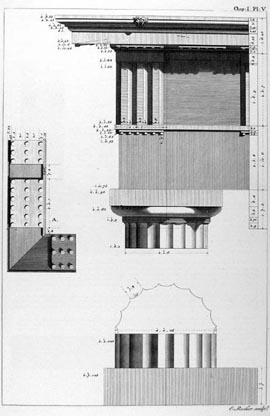

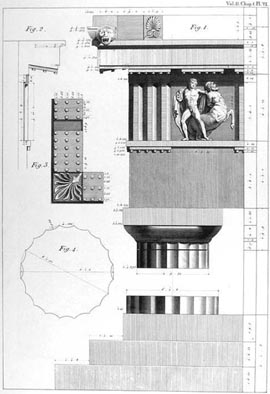

Then follow the plans, sections, elevations and details , |

|

|

|

|

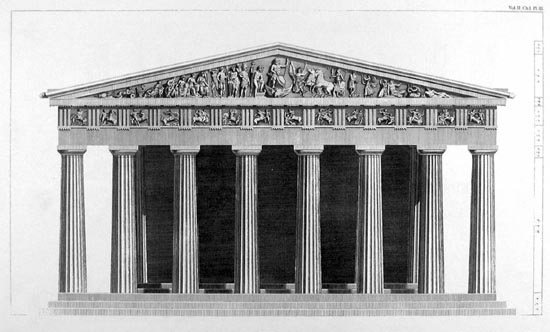

The Parthenon appears in the second volume. It start with a perspective view, |

|

And then, as in the other cases, the plan, the elevations, sections, details,... |

|

|

|

|

|

Origin of the images:

- Robert Wood, The Ruins of Palmyra, Farnborough, Gregg, 1971 (fac. from London, 1753)

- Robert Wood, The Ruins of Balbes , Farnborough, Gregg, 1971 (fac. from London, 1757)

- James Stuart, The Antiquities of Athens, New York , Benjamin Blom, 1968 (fac. from London, John Haberkorn, 1762)

Recommended bibliography :

- R. Weiss, The Renaissance discovery of classical

antiquity, New York, 1969

- Andrew Wilton y Ilaria Bignamini, Grand

Tour. Il fascino dell'Italia nel XVIII secolo, Milan,

Skira, 1997

- Gigliola Pagano de Divitiis, "Cultura ed economia: aspetti del

Grand Tour", Annali di architettura,

n. 12, 2000

- Gigliola Pagano de Divitiis, "Cultura ed economia: aspetti del

Grand Tour", Annali di architettura,

12, 2000, pp. 127-141

- Jeremy Black, Italy and the Grand Tour,

New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2003

© by Francisco Martínez Mindeguía’s texts

>> Back to the top of the page

>> Back to Dibujos Ejemplares de Arquitectura