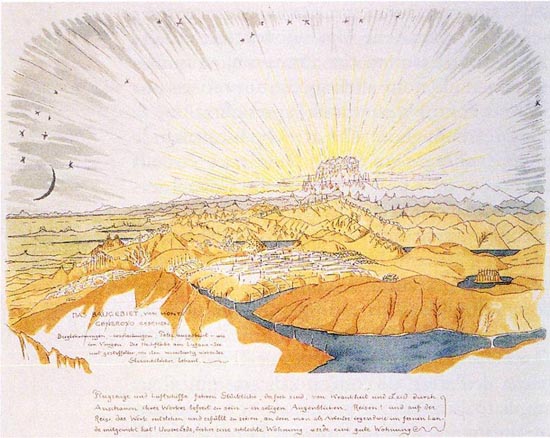

BRUNO TAUT, Architecture in the Alps, 1919

Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

|

|

|

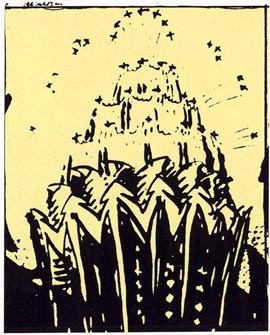

Bruno Taut,Alpine architecture, seen from the Monte Generoso, 1919 The drawing appears in Alpine Architektur, a book by Bruno Taut, in which he portrays his utopic project for a city in the Alps. This is the view from the Monte Generoso (lamina 17). Alpine architecture was a free project, solved with no apparent restrictions, no limitations owing to the place, material, or economy’s conditions. They were houses made of crystal on the mountains top, designed only for silent gazing and located next to the lakes, which reflected the buildings and the sparkling sunshine. These buildings were meant for the community of their inhabitants to build, just as cathedrals were built in the medieval age, a fantastic view of the construction of glazed temples in the Alps. In his exhibition, he introduces ideas of transparency, transformation, movement, and constant change and dissolution notions. The project does not have a justification of use; clearly, it is a reaction to industry. Its only use was to build and bring peace. In a part of the book, he says: PEOPLES OF EUROPE! The project has to be understood as a reaction to the processes that lead to World War I, and the following situation. It emerges from the belief that big industrial accumulations perpetuate the old social order, and they have to be replaced by a kind of decentralized community, following the ideas that had been accepted by socialists before the war. The Alps were a place far enough to build a new society. Here, crystal, transparency, and flexibility mean a purified and changed society, a reaction against the devastating effects of war. The project was a utopia, and Taut never expected it to be built. A few years before, in 1912, Taut met Paul Scheerbart, a visionary writer of novels and short stories, which described glazed architecture of mobile houses, which could rotate, and buildings that could rise and descend, structures that floated and moved through air, even cities on wheels., He published the book Glasarchitektur (Glass architecture) in 1914, dedicated to Taut. Taut’s book Alpine Architektur was also homage to Scheerbart, who passed away in 1915. This is a glazed architecture, but architecture of light as well, because of the light radiating out of this architecture. This luminous image also appears in other Taut’s drawings, |

|

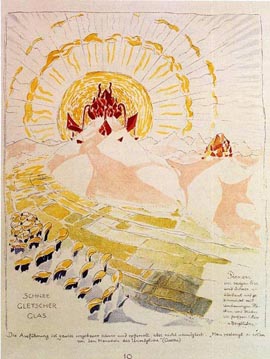

This is another image of Alpine architektur | |

|

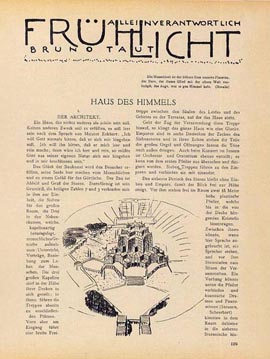

This is a drawing from 1920, entitled Idea of a house in the sky, which was the cover of the radical architecture magazine Frühlicht (dawn light), directed by Taut. Here, the topic of the shining light is repeated.

|

|

After that date, fourteen members of Arbeitsrat für Kunst started a sort of idealistic mailing. Taut suggested that “each and every one of us will draw and make remarks, in short periods of time, in an informal manner, and as we feel inspired, (…) the ideas that we would like to share in our circle.” The letters were known as Die gläserne Kette (the crystal chain), signed under pseudonyms, and the mailing lasted till December 1920. Many of them were published in Frühlicht, the magazine Taut directed. The lighting in the mountains was an idea which was also in Paul Scheerbart’ s writings, but it had implications long before. In Art History, light always had a clear religious meaning, whose origin is in the Bible. Its expressive content was widely used in Baroque painting, Architecture, and Literature. Light was related to power in Louise XIV’ s reign (The Sun King) during 17th century, and to knowledge in the 18th century (the century of lights). The light of these drawings is more like the dazzling light of birth, the rise of a new society... of the sublime. Before World War I, Italian futurists had already adopted the expressive and symbolic value of light, |

|

|

After the war, light was adopted by most of the expressionist artists. Taut’s experience was later followed by Hans Scharoun, the Luckhardt brothers and others. |

|

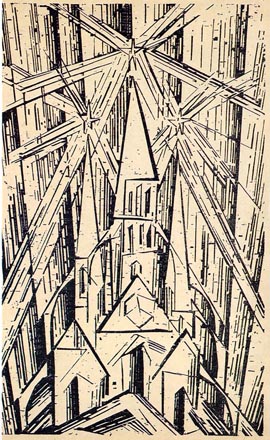

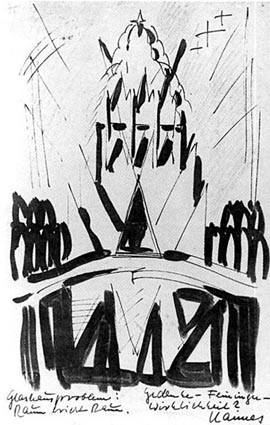

This drawing is a xylography by Lyonel Feininger, in 1919, which appeared in Weimar’s Bauhaus manifest. It portrays a cathedral, from whose towers, representing painting, sculpture, and architecture, light emerges, brightening all surroundings. The image of the cathedral comes from the book Formprobleme der Gotik (Form in Gothic), written by Wilhelm Worringer, published in 1912, and it symbolizes the common work done by people’s efforts. | |

|

Hans Scharoun is another example of the use of light in that sense. The drawing’s title is Glass Construction, 1919. |

|

|

Hans Scharoun’s Thought for the house of the people, published in Frühlicht, in 1919-1920. | |

|

Hans Scharoun’s Three by Three Dimensional Glass House, published in Frühlicht, issue number 10, in 1920. | |

|

Hans Scharoun’s "Glashausprolem," from the series Die Gläserne Kette (Glass Chain), around 1920.

|

|

|

(See the artificial lightening outside the buildings in Georgia O'Keeffe, American Radiator Building, 1924 )

Recommended bibliography:

- Dennis Sharp, Modern architecture and expressionism,

London, Longmans, 1966.

- Franco Borsi, Architettura dell'espressionismo,

Genova and Paris, Vitali e Ghianda y Vincent Fréal, 1967.

- Oswald Mathias Ungers, "Tres opiniones sobre el fenómeno

expresionista", Nueva Forma, nº

68 (Sep. 1971), p. 2-5.

- Wolfgang Pehnt, Architecture expressionniste,

Paris, Hazan, 1998 (original 1973)

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, "Paul Scheerbart's Architectural Fantasies",

The Journal of the Society of Architectural

Historians, vol. 34, n. 2, 1975, pp. 83-97.

- Tim Benton, Las Raíces del Expresionismo,

Madrid, ADIR, 1983 (original 1977).

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, "The Interpretation of the Glass Dream-Expressionist

Architecture and the History of the Crystal Metaphor", The Journal

of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 40, n. 1,

1981, pp. 20-43.

- Ignasi de Solà-Morales i Rubió, La

Arquitectura del expresionismo, Barcelona, ETSAV, 1982

- Rosemarie Haag Bletter, "Expressionism and the New Objectivity",

Art Journal, vol. 43, n. 2, 1983,

pp. 108-120.

- Wolfgang Pehnt, Expressionist architecture

in drawings, London, Thames and Hudson, 1985.

- Ada Francesca Marcianò, Hans Scharoun

1893-1972, Roma, Officina Edizioni, 1992.

- Winfried Nerdinguer et alt., Bruno Taut

1880-1938, Milan, Electa, 2001.

© of the texts Francisco Martínez Mindeguía

© of the English translation Ruth Costa Alonso, Francisco Martínez Mindeguía, and Antonio Millán

>> Back to the top of the page

>> Back to Dibujos Ejemplares de Arquitectura